I talk a lot about adaptation with my athletes, often reminding them that the goal of training isn’t to train the most, it’s to adapt the most. But what does that actually mean?

You can think of a muscle (or bone, or tendon, or ligament, or cell, or whatever) as a brick wall.

This brick wall has a function, just like our muscle does. The wall’s job is to keep some stuff on one side, and some stuff on the other side. You know, basic wall shit.

When we exercise, we’re actually breaking down our tissues. We’re making them less capable at their function. In our brick wall analogy, this is like taking bricks off the top of the wall. After exercise it’s going to be less good at keeping some things on one side of the wall because it’s smaller.

When we then rest after the exercise, we start repairing the wall, replacing the bricks that we knocked off during our workout. We need to get it back to as good as its job as it was before we knocked the bricks off. After a certain period of time, our wall is back to its nice and strong place that it was before we knocked part of it down.

But remember that the point of training isn’t to stay the same. It’s to get better. In our wall analogy, we’re trying to build a bigger/stronger wall, which will be better at its function.

So what do we need to do to add more bricks after we’ve repaired the damage? We need to do fucking nothing, is what! This is what makes the human body so cool! Our body knows that whatever tried to get through the wall hurt the wall a little bit, so it wants to build the wall up stronger so that next time it doesn’t have to repair it as much. The body is very proactively lazy. It will do a fair bit of work now in order to do very little later. And all we need to do to let this happen is to keep resting after the wall has been repaired, and it will keep adding bricks until it’s a little stronger than it was before. The additional bricks added above baseline is called adaptation or super-compensation.

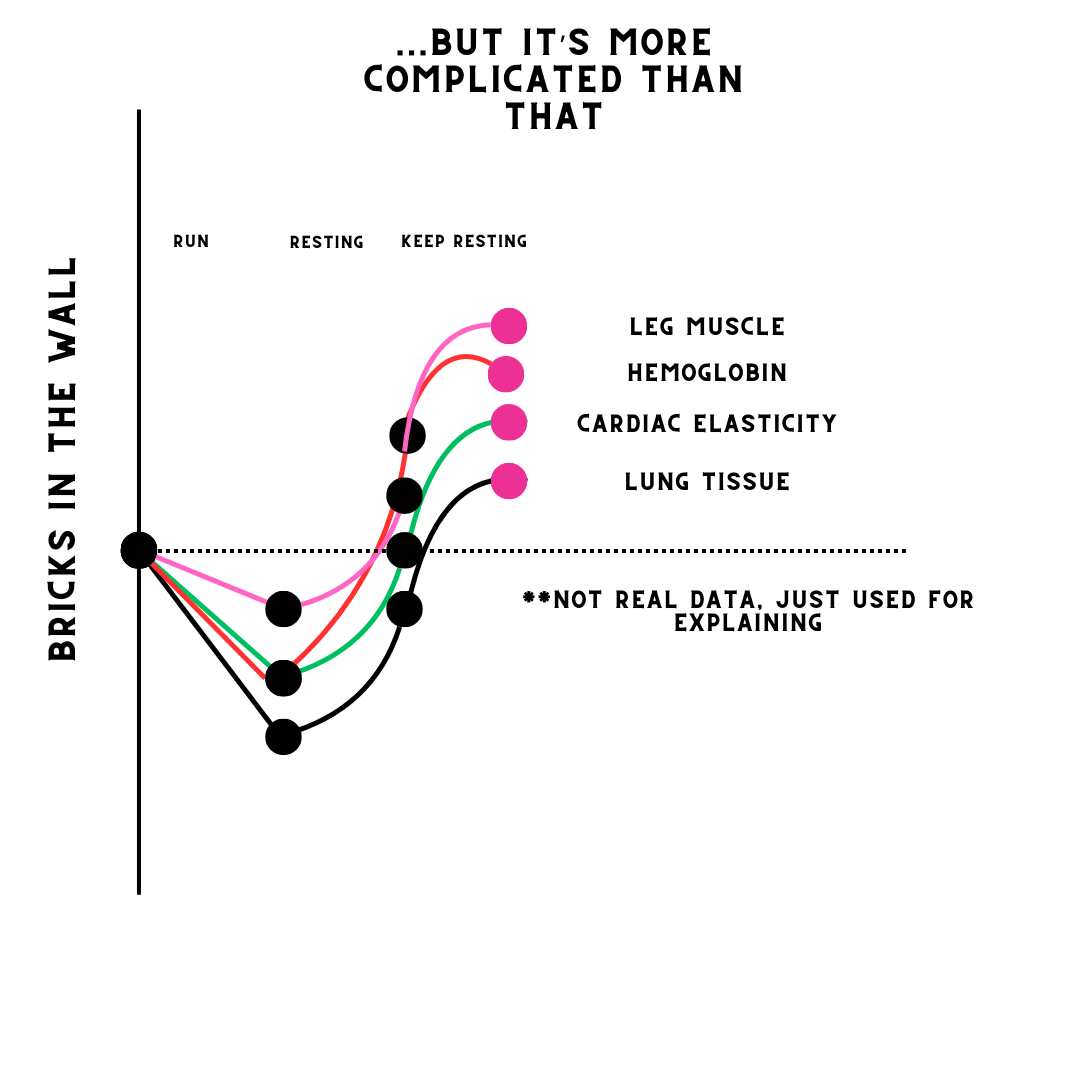

It’s important to remember that while this analogy is fairly accurate, it’s also simplistic. One challenge of training is that we’re made of a trillion different brick walls, and all of them lose and add bricks at different speeds. So one workout might knock five bricks off one wall, and 100 off another. And then that first wall might gain a brick an hour, and that second wall might gain 10 bricks an hour. So after training, it’ll take the first wall five hours to get back to baseline, but the second wall takes 10 hours! If you decide to train again after six hours, when the first wall is stronger, you’ll be training too soon for the second wall.

As I mentioned above, the body is quite lazy. And, really, it’s for good reason. You see bricks are expensive, and maintaining unnecessarily large bricks walls for no reason is wasteful. For this reason, if nothing has tried to get past a wall in a while, the body is actually going to start pulling some bricks off the top of the wall and using them for something else.

If you have a wall that you want to be super strong, but you knock bricks off it rarely, that wall isn’t going to have many bricks. This is called under-training.

If you knock bricks off the wall before it’s back to 100%, this is called over-training. In the training literature over-training is broken down into three rough categories.

First, is over-training-syndrome (OTS). OTS is some big bad shit. This happens when you over-train for so long that the body doesn’t even bother putting bricks back on the wall. The definition of OTS is “a significant loss of performance that takes weeks or months of rest to resolve.” OTS also takes some pretty hard-headed shit to get to. You need to take more bricks off the wall than you add (through too much training, or not enough resting, or not enough fueling, etc) for months in order to really break the system to true OTS.

Second, what many self-coached endurance athletes will see at some point (or, live in), is non-functional-over-reaching (NFOR). Remember how all the brick walls break down and rebuild at different speeds? Well if you knock down some of the big and slow-to-recover ones enough, you will need so long to recover that some of the faster-to-recover ones will already start de-training, resulting in a net loss of performance. This is why avoiding big swings in fatigue is so important, and why “hero workouts” don’t work!

Third is functional-over-reaching (FOR). FOR is when you carry a little fatigue into the next workout, but purposefully. You don’t quite have all the bricks built back up from yesterday’s workout, but you know that tomorrow is a rest day, and so even though your walls are down a little for today’s workout, you think it’s little enough that tomorrow’s rest day will result in all the walls being built back stronger.

There is some controversy around FOR. There are some quite good coaches who argue that it doesn’t exist, and that almost any form of fatigue carrying from day to day is likely to result in less adaptations than if you added fatigue slower. There are a lot of good arguments to be made here. For example, remember that when your walls are missing even a couple bricks, your performance is worse! So if you’re training with walls lower than possible, you’re executing workouts slower/shorter than possible.

If you’re my age or older (I was born in ‘83), you’re almost certainly familiar with NFOR. The thought in the 80’s and 90’s (and even early 00’s), was that you could smash yourself into pieces for weeks, and then take a rest week and “bounce” back up to really high performance. And while this technique did work for some people, for the vast majority of people (even the vast majority of elites), it’s far less effective than staying closer to the edge of FOR and not-over-reaching-at-all.

This is certainly something I’ve changed my philosophy on. Coming up through the prime years of NFOR, I used to believe that if someone wasn’t responding to training, you add more training, and make sure they’re getting their rest weeks. Huh, turns out that didn’t work, especially for athletes who live at any kind of altitude.

Since I’ve switched to more of a “FOR or less” strategy, my athletes are seeing much larger and more consistent gains on average.

Turns out drowning in fatigue isn’t that useful.

Questions?

Your skepticism of FOR really resonates with me. I'm a 52 yo ski mountaineer/peakbagger who started structured run training early this year using teh typical 3 on 1 rest week schedule. Completed my first 50K but also ran pretty deeply into OTS and don't feel like I built a lot of fitness given the effort. Pretty sure 99% of that kind of overreaching.

Hi, Joe. Q: After establishing some history with it, is the Training Peaks 'Form' value useful to help decide training load on a given day? I.e. Four days after a big effort, TP Form = (-11). Factoring that with how I feel, an easy 1 hr effort seems like the max for today, or maybe that's still too much for recovery. Curious how much weight the Form value should carry for training decisions.